What is Pompe Disease?

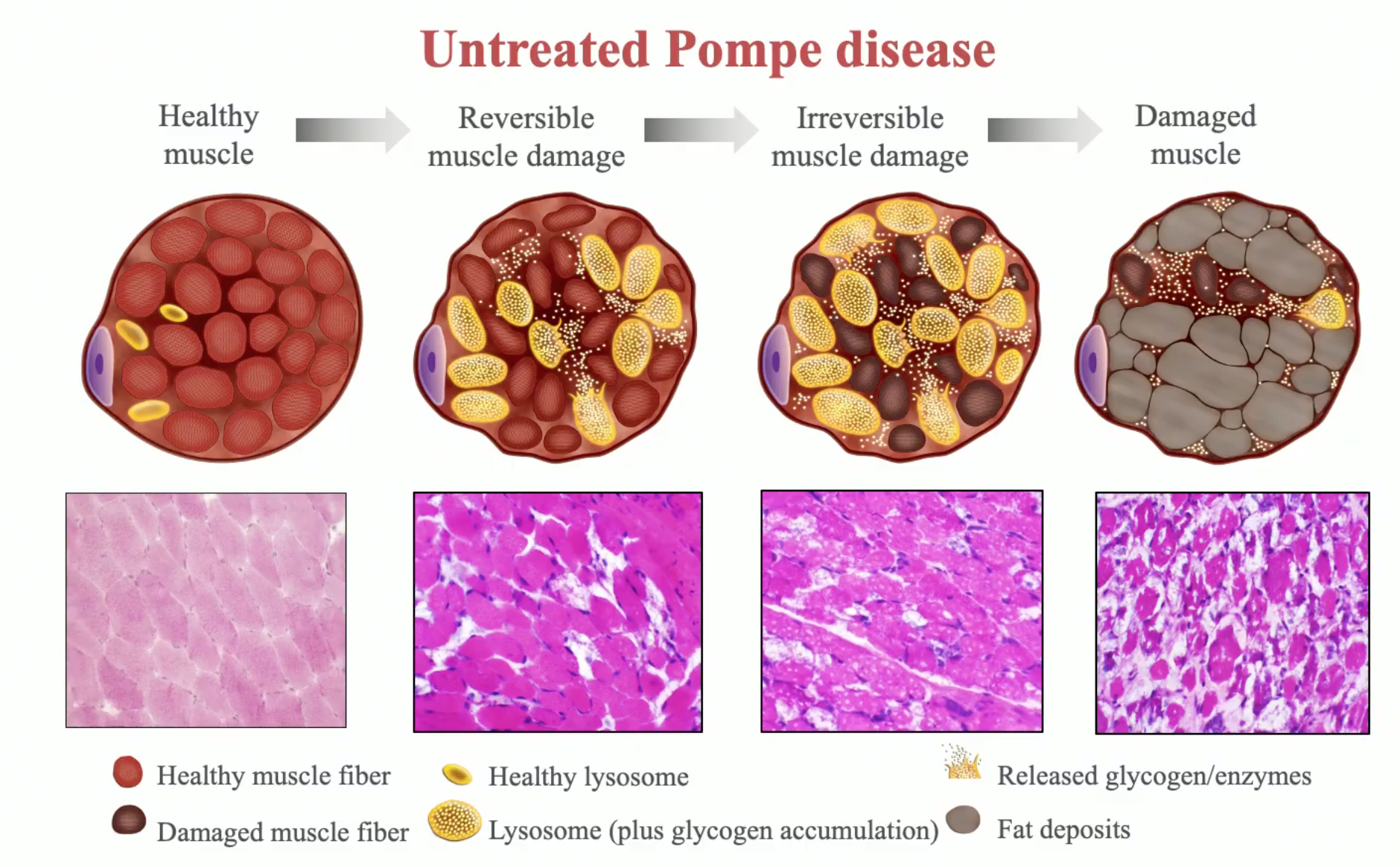

In the general population, Pompe disease occurs at a rate of about one in 40,000 people. The late onset form of the disease occurs in about one in 57,000 births, and the infantile onset form occurs in about one in 140,000 births. Pompe disease affects males and females equally, and in most cases, both parents of an affected child are asymptomatic carriers of the disease. It is caused by mutations in a gene that makes an enzyme called acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA). Normally, the body uses GAA to break down glycogen, a stored form of sugar used for energy. But in Pompe disease, mutations in the GAA gene reduce or completely eliminate this essential enzyme. Excessive amounts of glycogen accumulate everywhere in the body, but the cells of the heart and skeletal muscles are the most seriously affected. Researchers have identified up to 70 different mutations in the GAA gene that cause the symptoms of Pompe disease, which can vary widely in terms of age of onset and severity. The severity of the disease and the age of onset are related to the degree of enzyme deficiency.

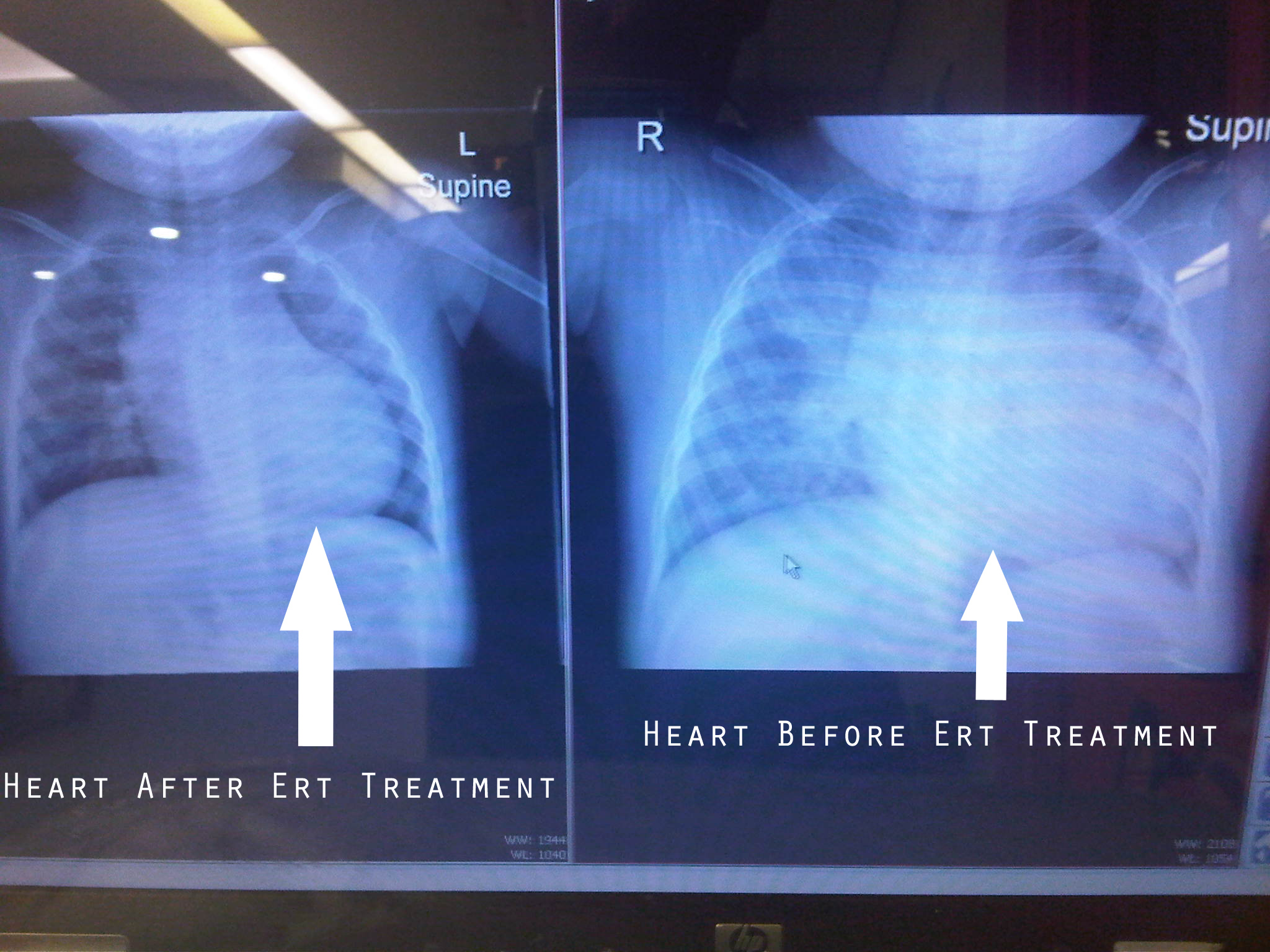

Early onset or infantile Pompe disease is the result of complete or  near complete deficiency of GAA. Symptoms begin in the first months of life, with feeding problems, poor weight gain, muscle weakness, floppiness, and head lag. Respiratory difficulties are often complicated by lung infections. The heart is grossly enlarged. More than half of all infants with Pompe disease also have enlarged tongues. Most babies with Pompe disease die from cardiac or respiratory complications before their first birthday.

near complete deficiency of GAA. Symptoms begin in the first months of life, with feeding problems, poor weight gain, muscle weakness, floppiness, and head lag. Respiratory difficulties are often complicated by lung infections. The heart is grossly enlarged. More than half of all infants with Pompe disease also have enlarged tongues. Most babies with Pompe disease die from cardiac or respiratory complications before their first birthday.

Late onset (or juvenile/adult) Pompe disease is the result of a partial deficiency of GAA. The onset can be as early as the first decade of childhood or as late as the sixth decade of adulthood. The primary symptom is muscle weakness progressing to respiratory weakness and death from respiratory failure after a course lasting several years. The heart may be involved but it will not be grossly enlarged. A diagnosis of Pompe disease can be confirmed by screening for the common genetic mutations or measuring the level of GAA enzyme activity in a blood sample—a test that has 100 percent accuracy. Once Pompe disease is diagnosed, testing of all family members and consultation with a professional geneticist is recommended. Carriers are most reliably identified via genetic mutation analysis.

Is there any treatment?

Individuals with Pompe disease are best treated by a team of specialists (such as cardiologist, neurologist, and respiratory therapist) knowledgeable about the disease, who can offer supportive and symptomatic care. The discovery of the GAA gene has led to rapid progress in understanding the biological mechanisms and properties of the GAA enzyme. As a result, an enzyme replacement therapy has been developed that has shown, in clinical trials with infantile-onset patients, to decrease heart size, maintain normal heart function, improve muscle function, tone, and strength, and reduce glycogen accumulation. Myozyme© (alglucosidase alfa), an Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT) for Pompe Disease has received market approval in a growing number of countries.

What is the prognosis?

Without enzyme replacement therapy, the hearts of babies with infantile onset Pompe disease progressively thicken and enlarge. These babies die before the age of one year from either cardiorespiratory failure or respiratory infection. For individuals with late onset Pompe disease, the prognosis is dependent upon the age of onset. In general, the later the age of onset, the slower the progression of the disease. Ultimately, the prognosis is dependent upon the extent of respiratory muscle involvement.

Signs and Symptoms

- Infants typically have extreme muscle weakness and a “floppy” appearance. X-rays usually reveal a greatly enlarged heart. Other symptoms include breathing difficulties, trouble feeding, and a failure to meet developmental milestones such as rolling over and sitting up.

- Children and adults tend to have greater variety in their symptoms, often including weakness of the leg and hip muscles, leading to difficulties with mobility, as well as breathing difficulties. Older patients rarely have the heart problems typical in infants.

If the infant sufferer is only one year old, the first year is very critical. The progression rate can be fatal by one year of age. It may result in significant distress and often premature death. Early in infancy, the rate of progression is very rapid. Without treatment, survival rate is poor. Children and adults usually display more gradual and variable rates of disease progression.

Pompe disease is always progressive, meaning that its symptoms worsen over time. In general, the earlier in life the symptoms appear, the faster the rate of progression. Most infants affected by the disease experience very rapid progression, and they rarely survive past the age of 1 year.

When symptoms first appear later in life (children or adults), the rate of progression is generally slower than in infants, although there is great variability across different people. In addition, an abrupt and rapid decline can happen at any time, so careful monitoring of the disease’s progression is very important. Whether the disease progresses fast or slowly, eventually movement and breathing difficulties worsen over time.